When data breaches and permission-related security incidents keep happening, it’s a clear sign we’re not handling access controls right. Let’s revisit some breaches and consider the consequences of having overly permissive identity and access management (IAM) policies, even in environments that might not seem like candidates for attacks.

In 2019, Capital One suffered a data breach that exposed the personal data of more than 100 million customers. This attack didn’t require intricate social engineering or multiple hacking tools; it started with a misconfigured web application firewall (WAF) that allowed the attacker to access an internal instance of Amazon S3. The primary issue? IAM roles that were set far too permissively, without strict need-to-know access. This enabled the attacker to escalate privileges from a relatively minor access point to major data assets.

In 2023, Toyota disclosed a data exposure affecting databases and resources that contained private customer information. The underlying problem? IAM policies granted overly broad access in non-production environments with few restrictions. These permissions went unchecked, leaving sensitive resources exposed to the public. The rationale behind these permissive policies was that non-production environments were “lower risk.”

The Path of Least Resistance

It is easy to see how this happens so frequently because setting strict IAM permissions can be time-consuming and challenging. Let’s say we have a cloud application in AWS with multiple services that need unique permissions to access different AWS resources, like S3 for storage, DynamoDB for databases and SQS for messaging. The recommended approach is to create custom IAM roles tailored to each service and ensure that individuals, applications or systems only have the essential access necessary to perform their tasks, reducing security risks by:

- Minimal access by default: Grant only essential permissions for each role or application, avoiding broad access even in non-production environments.

- Dynamic permissions: Regularly review and adjust permissions as roles and requirements evolve, maintaining minimal necessary access.

- Access revocation: Remove permissions when no longer needed to prevent “permission creep” over time.

In the event of a data breach, the biggest benefit of granting the least privileged access is the reduction in the severity of a breach. Even if an attacker can find a way to make your Lambda invoke code if the function barely has any permissions, then the damage that can be done with the ability to execute code is extremely limited, minimizing breach impact.

Here’s where it gets complicated. Implementing least privilege requires an application’s requirements specifications to be available on demand with details of the hierarchy and context behind every interconnected resource. Developers rarely know exactly which permissions each service needs. For example to perform a read on an S3 bucket, we also need permissions to list contents of the S3 bucket.

Figuring this all out can involve trial and error, checking logs, updating roles and re-deploying each time a missing permission error occurs. In addition to this, some services might require indirect permissions. For example, if Service A interacts with Service B, Service A might need permissions to access resources that Service B relies on. This can lead to broader permissions across the chain, making it difficult to isolate access cleanly.

With the pressure to move quickly, the path of least resistance is to grant broad access, justifying this by suggesting that it will be tightened up later. But too often, it isn’t.

It’s Not Enough To Be Reactive

This is where we begin to be reactive and apply tools that scan for misconfigurations. Tools like AWS IAM Access Analyzer or Google Cloud’s IAM recommender are valuable for identifying risky permissions or potential overreach. However, if these tools become the primary line of defense, they can create a false sense of security.

Most permission-checking tools are designed to analyze permissions at a point in time, often flagging issues after permissions are already in place. This reactive approach means that misconfigurations are only addressed after they occur, leaving systems vulnerable until the next scan.

In reality, they only flag exceptionally broad permissions and lack the context to assess more nuanced configurations and determine the absolute minimum levels of access required. For instance, the IAM Access Analyzer can flag issues such as an S3 bucket being publicly accessible. It’s not wrong to flag this as an issue to be checked, but the tool lacks an in-depth understanding of whether the permissions granted really do align with application needs.

In this example, if we could provide the right context, then we have options:

- Restrict more sensitive actions like PutObject or DeleteObjectto specific users or roles only.

- Restrict access to specific IP ranges that correspond to trusted sources.

- Set conditions in the bucket policy to allow access only during certain times, limiting the exposure window if appropriate.

Least Privilege by Default

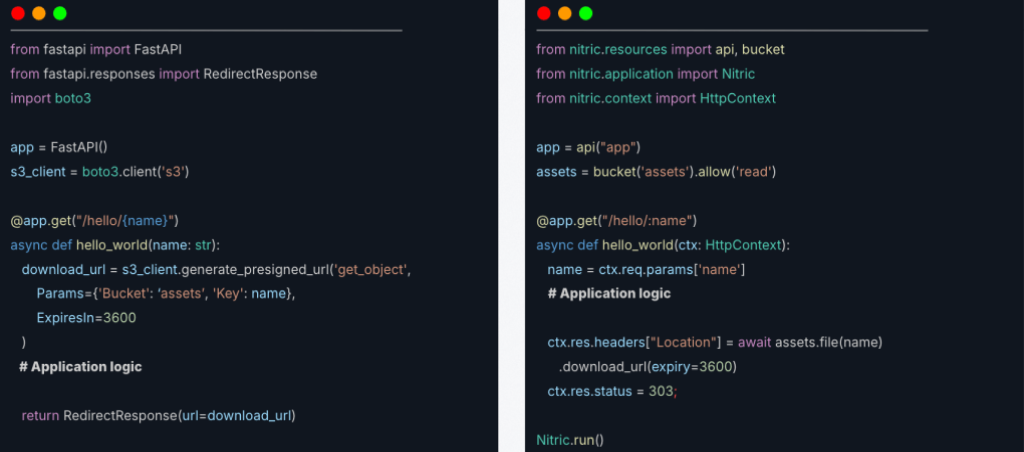

The solution lies in rethinking the way in which we wire up these relationships in the first place. Let’s take a look at two very simple pieces of code that both expose an API with a route to return a pre-signed URL from a cloud storage bucket.

The example on the left is using the FastAPI framework, and the example on the right is using Nitric framework. Both functions are equivalent; they will return a pre-signed URL to download a file.

The key difference is that the Nitric example includes an additional declaration indicating how the function intends to use the bucket: .allow(“read”). This declaration of intent is the context required to generate the relationship hierarchy between the two resources and without it, the handler will not have access to the bucket.

While this approach requires minimal effort, it represents a distinct shift in the way we think about access control. By allowing developers to specify their intended use of a resource directly alongside its declaration, they can clearly indicate what they want the application to do with that infrastructure. This proximity to the declaration simplifies context management, as developers don’t need to mentally map the entire system. Instead, at deployment time, we have an exact record of the permissions each application requires.

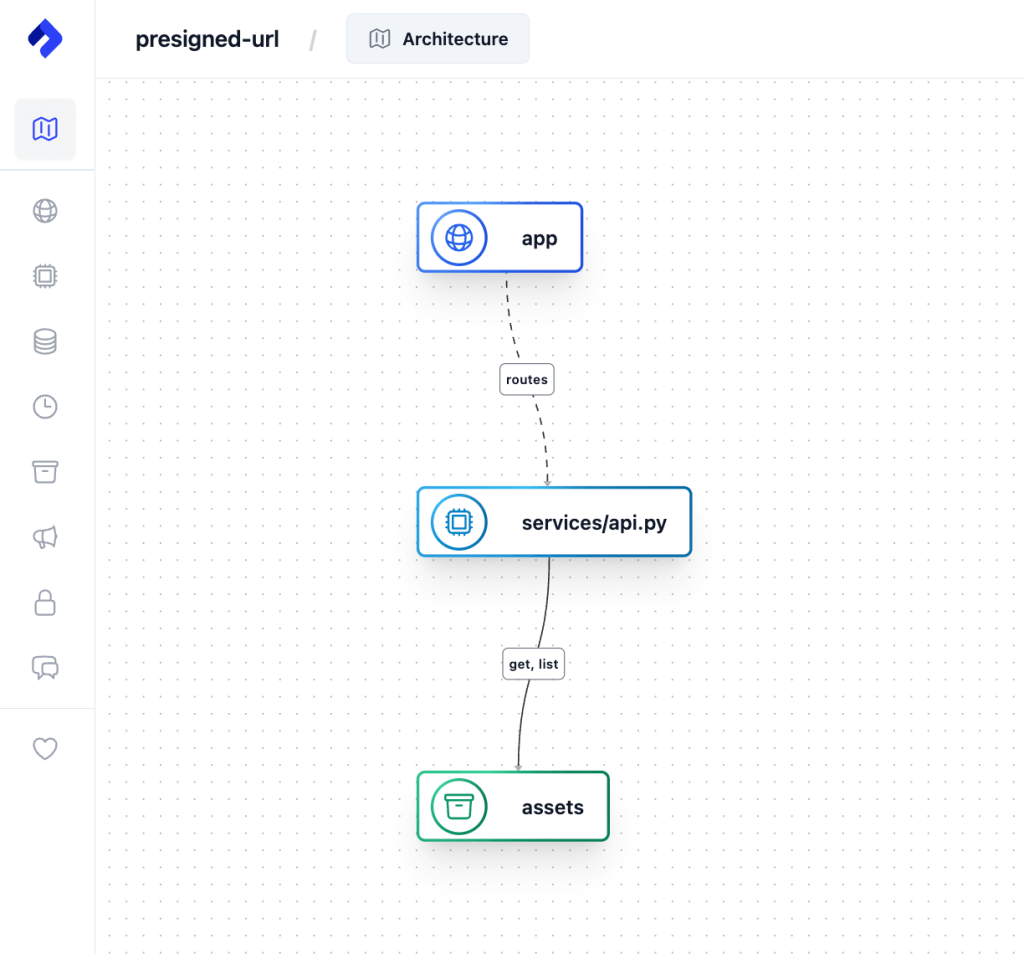

Taking it a step further, we can generate JSON and even visual representations of this relationship map.

To see this in action, check out the Nitric Quick Start guide, which will walk you through setting up a project, creating a new stack and generating Infrastructure as Code like Pulumi or Terraform that grants least privilege by default for your application.

Checkout the latest posts

Why I joined Nitric

Why I left the corporate world to join Nitric

Build Azure Infrastructure Using AI and Terraform

Learn how to leverage AI and Terraform to build and deploy Azure infrastructure directly from your application code with Nitric.

GenAI Made Terraform More Relevant Than Ever

Infrastructure as Code is more alive than ever, but it is no longer something teams should write line by line.

Get the most out of Nitric

Ship your first app faster with Next-gen infrastructure automation